Issue 18

Kiana Tofighi

Ever since the Assyrian onslaught, and the dispersion of Jews across the Globe more than 2700 years ago, Jewish settlers in various countries have adapted greatly to their environment, being influenced by their surrounding culture, yet preserving their own traditions and religion. Among Jews of various nations, Jews of Iran may be regarded as significant due to two primary reasons. Firstly, based on historical evidence, Iran was the land of the outset of the Diaspora, such that the Jews of the ten tribes of the House of Israel, exiled from their homeland, settled in Iran and from there migrated to other countries like China, India, and Russia. Secondly, Iran is the birthplace of the Karaite movement in Judaism, which spread throughout the world. Despite all this, little or no attention has been devoted to Iranian Jewry. Noting the fact that more than 65% of the Iranian Jewish population has left Iran in the last 25 years, the attempt is to unveil the reasons behind the sudden mass emigration of Jews whose settlement in Iran exceeds 2500 years. Over the course of the next two issues, you will be reading a rather condensed version of a more elaborate research paper surrounding the Iranian Jewish community. The goal is to shed light on the way Persian Jews have settled in Toronto both as individuals as well as a community, and their relationship both to the old environment and to the new one by elaborating on a series of seven personal interviews. Before examining the community in Toronto more closely, we will briefly review the history of Iranian Jewry, for its study is not only helpful but also necessary for identifying the uniqueness of this group and understanding them as a whole.

History of Iranian Jewry

Persian Jews are recognized as the oldest and most established minority in Iran, for they have lived in Iran for more than 2500 years. The first Jewish settlers in Iran were those captives in Babylon (after the destruction of the first Temple) who were liberated by King Cyrus in 539 BCE when he conquered Babylon. So the story goes that King Cyrus of Iran crossed the Tigris River, fought against and defeated the Babylonian army. However, unlike how his Babylonian counterpart King Nebuchadnezzar had done so 50 years earlier, he entered the city not as a vicious conqueror but as a tolerant leader. He freed all slaves including all Jewish captives and issued a proclamation in Babylon, the original text of which is know as the “Cyrus cylinder” and a replica of which is kept at the United Nations building in New York. In this proclamation which some argue is the firs international charter of human rights and equality, Cyrus grants freedom to all nations under his rule. Hence, he was hailed as a liberator by the Jewish slaves freed from bondage and was given the title “God’s anointed” in Isaiah 45:1-4 in the Bible. Although the majority of Judean captives, who were exiled to Babylon 50 years earlier, returned to Jerusalem to rebuild their homeland, some accompanied Cyrus as their new ruler to Persia. For more than two centuries the descendants of Babylonian Jews flourished under the rule of the Achmenian Dynasty. In later centuries however, after the fall of the Persian Empire and its invasion by Greeks and later on by Muslim Arabs and with the propagation of Shi’ism in Iran, the circumstances changed drastically for Persian Jews. Though there were isolated and regional cases of discrimination and hardships, Muslims and Jewish Iranians lived in relative harmony even after the Arab invasion.

Jews in Shi’ite Iran

Even after the arrival of Islam in the middle of the 7th century AD, the status of Jews did not change much. In 1501, King Esma`il founder of Safavid Dynasty (r. 1501-1722 AD), declared the Shi’ite sect as the dominant form of Islam in Iran. With the rise of Shi’ism, status of religious minorities changed for the worse in Iran. This transition marks the beginning of 450 years of marginalization, hardship and alienation of Jews in Iran. The Safavid often practiced policies that put tremendous restrictions on Jews concerning trade, employment, even attire. Jews were required to dress distinctively from Muslims and pay higher taxes know as jeziah. During the reign of the Safavids, communities in major Jewish centres like Isfahan and Hamadan were forced to convert to Islam. As a result, many Jews converted to Islam, observing their faith and customs only in secret.

The concept of nejasat (spiritual impurity) was produced and introduced by the Shi’ite think tank under the Safavid rule. Various religions consider certain substances or objects to be impure. For instance in Judaism, leprosy, menstruation, carcasses, idolatrous objects and unlawful food and drinks are considered impure. In mainstream Islam, wine, meat not ritually slaughtered, blood, feces, and urine fall under the impure category. In Shi’ism however, corpses and non-Shi’ites are added to this list! In the Qu’ran, a verse in al-Moshrekun 1:28 deals with this subject: “O you who believe, the idol worshipers are surely unclean, so they shall not approach the sacred Mosque”. Shi’ite commentators have brought all non-Shi’ites under this category even though the term idolaters in this verse explicitly refers to polytheists. Scholars believe that this obsessive concern of being polluted by infidels which ironically includes Sunni Muslims too, is restricted only to Iranian Shi’ism. (Lewis, 1981, p. 34) According to this school of thought, the primary source of the concept of “impure man” lies in the pre-Islamic religion of Zoroastrianism, founded in 6th century BCE. (Soroudi, 1994, p. 154) Zoroastrianism like Hinduism has similar concept of impure man as a result of the caste system. The three main castes in Zoroastrian Iran were segregated nobles from priests from nomads. In this system a person from a lower caste is considered to be impure by members of the higher caste. Although differently based, there is a great degree of similarity between Shi’ite and Zoroastrian practices. Nejasat prohibited all religious minorities including Christians, Zoroastrians and Sunnis but especially Jews from coming into contact with Shi’ite Muslims, touching food in Muslim shops or selling edibles to Muslims. Furthermore, they were banned from using Muslim public baths, drinking from wells or walking in the street on rainy days. What gave these decrees their particular intensity with respect to Iran’s Jewish community was the impressive influence of anti-Semitic Europeans in Safavid Iran at the time of the Spanish Inquisition.

The Qadar Dynasty, which ruled from 1795 to 1925, continued the harsh anti-Jewish policy of the preceding Dynasty. Under Qadar rule, Jews were viewed as ‘ritually unclean’ and were forced to live under harsh discriminatory policies. As a result of this kind of prolonged prejudice and injustice, the community suffered severely. In such dismal and gloomy era, the complaint of Iranian Jewish spiritual leaders to Alliance central committee in France once again brought hope to the despaired community. Alliance Israellite Universel, found in 1860 in Paris by Adolph Crèmieux, was an organization for international Jewish solidarity whose main goal was to “struggle for worldwide Jewish emancipation and the elevation of their intellectual level”. (Levy, p. 452) In an agreement between Adolph Crèmieux and the Nasir-al Din Shah of Iran in 1873, the Alliance central committee granted permission to establish its first school in Tehran and to invite four Jewish youths aged 12-15 to Paris to attend school. “These individuals [would] receive instruction necessary for the administration of the Alliance school at Tehran”.1 The Alliance established its first school in Tehran in 1898. Gradually, through the aid of their European brethrens, the situation for Persian Jews somewhat improved. With the operation of a network of about 20 schools across Iran in the early 20th century, the tables turned for this small but significant minority. At a time when the majority of the Iranian population was illiterate and the state was at its lowest, a new generation of educated Jews rose. In short, Alliance schools contributed greatly to the raising of the cultural and economic standards of Persian Jewry. It was this group of intellectuals who later on were viewed with much praise by the founder of the Pahlavi Dynasty, Reza Shah.

After centuries of misrule by its former corrupt rulers and the war from 1914-1919 BCE by foreigners on its soil, Iran on the eve of the 20th century was a deprived, ruined nation on the verge of disintegration. In 1921, Iran a country “as large as France, Germany and England put together, was traversed by no railways”.2 Its roads were hardly anything but camel tracks. War, famine and disease had depleted the majority of the population. In 1922, an overestimate of the population of such vast country had been 10 million, the majority of whom were illiterate peasants. The country was under the influence of powerful Imperial colonists like Great Britain and Russia. In this turmoil, the Muslim clergy did little to help. In fact, they were mostly concerned with serving their own interests. These fanatic leaders were those who, continuously encouraged the harassment of non-Muslim minorities, especially the Jews. In these times, forced conversions were old news and invoked no shocking reaction among the general public. When Reza Shah gained control in 1925, he set on his quest for modernism and reform, which Iran was in desperate need for. Reza Shah was striving to bring about a sort of renaissance in the cultural and political scene in Iran.

It is vital at this point to mention the importance of the Pahlavi Dynasty, to our discussion of the 20th century Persian Jewish immigrants in Toronto. The eight interviews, which will be studied in much detail, later on, were conducted with individuals who are of the Pahlavi generation. Even the older individuals among this group, spent their adolescence if not their early youth during the reign of this Dynasty. The significance of the Dynasty is that, the lives of all religious minorities including that of Jews improved greatly during its rule over Iran. It is also important to mention that the efforts of the aforementioned ruler to modernize Iran, opened many new doors to Iranian Jewry and emancipated them from anti-Semitic lashes of the fanatic “psedu-clergry”.3 In the 50 years of the Pahlavi rule, Jews along with other minorities experienced relative freedom of practice and lived lives free of persecution and harassment. They made incredible advancement in various fields namely science, literature and finance.

Whether Reza Shah’s moderate policies toward minorities and his provision of equal opportunities to all Iranians disregarding their faith, was based on good merit or diplomacy is unknown and irrelevant. What is clear though is his desire to bring about reform in as short a time as possible. One of his biggest obstacles in achieving this goal was the influence of the Shi’ite Orthodox clergy. Thus his first attempt was to completely separate religion from politics. Reza Shah believed that the religious class was preventing Iran from reaching enlightenment. So he tried to completely separate state from religion. One direct consequence of this was the emancipation of religious minorities which caused them to view him as a national savior.

Today, about 50 families live in the Toronto area, most of whom left Iran after the revolution in 1979, and the overthrow of the Shah of Iran, the second and last king of the Pahlavi Dynasty. It seems as though, most of the individuals in this group emigrated, based on the fear that the Islamic revolution would bring about unpleasant consequences. From the study of a personal interview with Mitra Talasazan, whose family has lived in Shiraz for many generations, one gets a flavour for the bitterness that the Islamic republic brought with it. She recalls: “after the revolution, Jews weren’t allowed to leave the country, especially in small cities.” She still has family back in Iran. She gave several examples of why any citizen concerned for his security and well being would have made the same decision her family did nearly 18 years ago. “In smaller cities, like Shiraz, Jewish residents were not [by law] permitted to sell their house”.4 She also indicated that “only one spouse could leave the country”5, while the other remained behind. Of course, there were always ways to go around a policy. For instance, they had to leave a security deposit, their house ownership documents in order to leave the country.6 However, the risk of losing the house always existed, if the family ever dreamed of not coming back. In fact, that is precisely the fate that befell upon them. They lost their house to achieve the freedom and the security that they were entitled to.

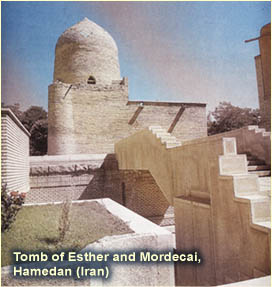

Based on statistics from the 1999 edition of Jewish Yearbook, there were just about 60,000 Jews residing in Iran before the 1979 revolution. According to the same publication, this number was reduced to 19,000 in 1991 while the population of Iran had rose to an estimate 61,000,000. Thus the Islamic revolution was in fact a major factor in the emigration of the Persian Jewish population. As it was mentioned previously, there existed several Jewish centres in various regions of Iran. In fact, even today it seems that the 19,000 Jews are divided up in several cities in Iran. According to Dr. H. Levy in Contemporary History of Jews in Iran, Tehran, Isfahan, Hamedan, Shiraz, Mashad, Damavand and Kermanshah all had in them incredibly strong communities of Jews. The reason for the population being so spread out is that during the course of history, several rulers especially in the Safavid Dynasty deliberately relocated the Jewish population from one region to another to prevent them from remaining intact and to further marginalize them by shattering their unity.

Form of the Community before Emigration

Out of the 7 interviewees, more than half left Iran as adults. Thus, their personalities, traditions, and habits were very much affected by their old environment. In fact, almost all the informants still have relatives in Iran, and therefore they all have in a way maintained their contact with their “homeland”. Today while the total number of Jewish Iranians has decreased tremendously, still the remaining population is divided up among several cities in various regions. There are certain common features in almost all Jewish communities, independent of the region in which they were located. Almost every city, which contained a Jewish community even as small as a few thousand, had a Jewish school established by the Alliance. In the capital, Tehran, “a very strong community existed”8 according to Sasani, a Tehran born Jew. He stated that about 4 to 5 permanent synagogues operated in Tehran. In addition there also existed 4 Jewish schools which were used only on Saturdays as a place to worship. These were mostly located in the central Tehran, the historically older part of the city, in which a large portion of the community resided.

The structure of the community in Tehran was very much different than those in the provinces. According to Sasani’s estimate, which of course seems to be a somewhat optimistic figure, the Jewish population in Tehran was at least 100 thousand. The significant point here is not the precise statistical figure of the Tehrani Jews. The point is that based on the personal opinion of Tehranian citizen, the Tehran community can be categorized as a large, strong and established body. Apparently the Jews were dispersed all over the city, during Sasani’s residence in Tehran. In other words, they were not all concentrated in one specific part of the city, but in fact scattered over a large area. However, there were areas in Tehran that had maintained their Jewish heritage. For instance, Cyrus Street, the former Tehran ghetto during Qadar Dynasty was still highly populated by the lower class of Jewish merchants who were economically less fortunate. According to Sasani, another Jewish area was located in central Tehran, near the Tehran University, which is a historically rich part of the city. Sasani stressed that social interaction; area of residence and economic activity was based on “wealth and social status”9. His statements can actually be supported with a passage from Dr. H. Levy’s work, Comprehensive History of the Jews of Iran: “During [Reza Shah’s] reign, many Jews prospered financially. Many Jews both in Tehran and in the provinces left the ghettoes and bought homes in town.”10 Sasani also stated that economic activities covered a wide range of fields in his time; Jews had various occupation, they were “…merchant, store owners, businessmen, physicians, teachers, and factory owners”11. Thus it is evident that in his time, doors of opportunity were wide open to the Jewish Iranians and unlike the past, they were not limited to a handful of professions; they were free to choose any occupation or further pursue their studies in any desired discipline.

Based on Sasani’s observed that the community in Tehran was so large, it was simply impossible for all its members to socially interact with one another. More realistically the population was fragmented based on social status, class and wealth. He explained that there were “no gatherings for all Jewish residents”12 of Tehran, implying social interaction was class-based. Sasani is the only Jewish Tehran-resident that was interviewed. Nevertheless other individuals, who had resided in cities other than the capital but had traveled to Tehran on occasion, not only did not give contradictory views, but also often presented a similar description of the community in Tehran. One women who was born and raised in a smaller town in western Iran, near the city of Hamedaan, stated “it was different in Tehran in a better way, there were a lot more Jews”13.

Mehry Hamedi, a woman in her mid-seventies was born and raised in Hamedan. Her family and her husband’s family have been inhabitants of Hamedan for several generations. Her portrayal of the Jewish community is quite different than that of Sasani’s. For one thing, the people of smaller towns were strictly abided by Jewish tradition and were very much bound to religious customs and ceremonies. Hamedi’s estimate of the total population of the town was “about 300 to 400 families” when she was living there. Being from a family of traders and merchants, Hamedi confirms that in the provinces back in her time, Jews provided for their families as “jewelers, fabric-dealers and traders”14. Her husband, Yaghoob Hamedi, though a well read informed senior, had also owned a drug store in their hometown. Though he agreed with his wife, Mr. Hamedi tried to make the picture clearer by indicating that during Reza Shah’s rule, when top students were sent to Europe on scholarships to attend University, “[about] 10 to 15 … were Jewish”15. These bright Jewish students presumably pursued fields like Medicine and Pharmacy and after returning to Iran became very successful professionals. Hamedi also stated that “[In] Reza Shah’s time, the blossoming of Iranian Jews began”16. Y. Hamedi was implying that as soon as the opportunity presented itself to this enduring group, the ambitious Jewish youth took full advantage of it and developed impressively in a relatively short period of time.

The community in Hamedan although small, had been extremely tight. The city possessed about 5 synagogues that were very much different from those in Tehran. The shuls17 were very plain and small, often composed of a few rooms. Each one was at most capable of holding no more than 200 to 300 persons. To satisfy the demand especially during religious holidays and prominent ceremonies, the Jewish Alliance school was also used as a centre for gatherings. There were no teahouses or restaurants for the Jewish towns-people to regularly meet and socialize at. It had been customary for the Jews to go to one-another’s houses, precisely like the Muslims. In addition to having synagogues and a Hebrew school, Hamadan like all other Jewish communities in Iran also had its own public bath as well as a butcher shop where kosher meat was prepared.

The Hamedi’s who consider themselves Orthodox stated that Jews of Iran living in the provinces “were all Orthodox”18. They attempted to provide further evidence for their statements by pointing out how synagogues were segregated in Iran and how Jews of Iran especially those of their generation, were very much bound to tradition. They were often highly religious, for they went to synagogue every Saturday and paid particular attention to all Jewish holidays. The Alliance school and all Jewish-owned stores shut down on Saturdays and other important holidays or mourning periods like Rushashanah, Yom Kippur, and Passover. Mrs. Hamedi interestingly mentioned that on those noteworthy Jewish holidays “out of respect for Jews”19 Muslims did not open their businesses and thus the city was shut down.

Another elderly lady, Fakhry Kashani, native of Kermanshah gave a similar impression of the community in her hometown. She indicated that Kermanshah had a very large and strong Orthodox community. She stated that “every Saturday all Jews went to synagogues”20 to worship where women sat separate from the men. Kashani, being much older than the Hamedi’s, described all religious ceremonies, feasts, holidays, and mourning customs. Altogether, in Kermanshah the Jewish population had a religious ceremony almost every month of the year. She mentioned Passover, Pourim, Rushashanah, Pessah, Shabu’ot, and several others.

In contrast to Hamedan, Kermanshan and Shiraz, Burujerd, which is a small town in the west, near Hamedan, contained a very small Jewish community, composed of less than 200 families. Rose Kamhi, born and raised in Burujerd is at most a woman in her early forties. Growing up in an extremely isolated and traditional environment, Kamhi is nevertheless an open-minded woman coming from an educated family. Kamhi declared that about 100 to 150 families lived in Burujerd, all of whom lived in a particular neighbourhood allocated to the Jewish population. Kamhi explained “only about one or two families lived in other areas [outside the Jewish neighbourhood]”21.

Kamhi’s family background is perhaps the most interesting among all other informants. Her father, being the only physician in town, was highly praised and respected by the Muslim majority in Burujerd, yet her family could not possibly escape limitations placed upon them for being Jewish, for these “unwritten rule”22 were merely realities of life. In fact her father’s family had been immigrants to Burujerd from another part of the country, Nahavand, a city in northern Iran. She revealed how “where my father lived, everyone thought that his family was Muslim. Several Muslims had approached them to ask his sisters’ hand in marriage. Because of this, they immigrated to Burujerd”23 for they could no longer keep up the charade.

Kamhi herself attended University in the city of Isfahan and completed her studies in laboratory sciences. Kamhi claims that in her town one relatively large synagogue was present that provided plenty of room for the small community. Like other synagogues in the provinces this one too was made up of a main room and a balcony to segregate men from women. The expenses of the synagogues were funded by donations from the community. Like those of Hamedan and Kermanshah, Kamhi does not deny that the Jews of Burujerd were Orthodox in practice. Evidently based on this description, the community of Burujerd had been extremely close. Regarding social class, Kamhi stated that “when it came to going to Synagogue for prayer, there were no class limitations”.24 She repeatedly stressed on the close bond of the people saying, “if one person had a problem, those who had the means united to provide help”.25 Nevertheless, in terms of social contact and interaction, surely social status did have some effect. The fact that one of the most prominent Shi’ite religious leaders, Ayatollah Burujerdi was a native of Burujerd, placed enormous restrictions on Jews in this city.

In terms of economic activity, although there were successful men of trade and educated professionals like her father the majority of Jews in Burujerd were financially oppressed. According to Kamhi most men in the community ran their own small businesses (i.e. kept a shop). Kamhi continued by indicating that Jews were strictly restricted from having anything to do with food. They mostly owned fabric or variety stores or functioned as whole-sellers in the bazaar.