Issue 20

Donya Ziaee

Student of Political Science and Middle Eastern Studies at the University of Toronto

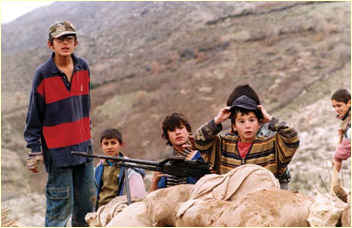

The state of the children of Bahman Ghobadi’s Turtles Can Fly is awfully daunting and dispiriting to witness. Many of them orphans, some destitute of limbs, some raped, and all emotionally-scarred, these defenseless children have endured immense, immeasurable, and interminable injustice and suffering. As the most vulnerable elements of the world’s greatest minority, Kurdish children are the principal victims of that nation’s continuous abandonment.

As Ghobadi’s account of the daily struggles of the children of a Kurdish village in Northern Iraq well demonstrates, this generation has been agonized not only by the crimes of Saddam Hussein, but also by the promises of the so-called “friend” of the Iraqi Kurds: the United States. While Ghobadi’s film is not an attempt to make direct and unsubtle political statements, the sight of the village and the sentiments of its people, following the U.S. occupation, scream of disillusionment, disenchantment, and unfulfillment.

Beyond Ghobadi’s striking portrayal of the relentless destitution facing too many Kurdish children, those vulnerable and indefensible gems, this viewer was also quite impressed by the film’s multiple references to the Iraqi Kurds’ desire to find access to Western news media. More generally, Turtles Can Fly can be said to be a superb display of the natural desire of all people to become aware of their fate – or at the very least to reach the same level of consciousness about future events as the rest of the world – through technology. We witness the entire village cooperate in putting together money and old radios to make the purchase of a satellite possible, and, when the satellite is finally installed, all other activities at the village come to a halt as everyone gathers to watch the news.

When the satellite fails to satisfy the curiosity of the villagers (the news is broadcast in the English language, at which no one is fluent), the village is practically dependent upon the predictions of Hengov, an armless boy capable of foreseeing the future. Indeed, Hengov’s entire existence in the film may be viewed as having served as an allegory of these people’s imposed detachment from the global consciousness, as well as their natural and justified desire to have access to information about developments that have the potential to inflict great pain and suffering unto them.

The so-called information revolution has undoubtedly not benefited all equally, contrary to what proponents of globalization would like us to believe. Globalization is often argued to have paved the way for an information revolution that is alleged to equalize prospects for affecting change at the international level, for the different actors involved. Yet, affecting such change depends not only on the ability to receive, but, more importantly, the ability to produce and disseminate information, as the process of establishing certain realities as worthy of dissemination is quite a selective one. Furthermore, there may exist a wide range of different interpretations on any given piece of information.

In times of war, in particular, the power to control and fabricate news is one of the most decisive factors in gaining or losing the support of public opinion. One need only point to the desperate, ruthless and persistent efforts by the U.S. to obstruct any images in opposition to its agenda in Iraq from hitting the airwaves – examples include the U.S. bombing and shelling of the al-Jazeera headquarters, as well as the obstacles that that government has posed for independent war reporting. Bahman Ghobadi succeeds in this film not only at portraying the unremitting and ardent desire of the Kurdish people to become aware of their ambiguous fate, but also manages to influence this fate by putting forth his own clear and distinct perspective on the situation.